Paulina Caro Troncoso highlights the encounters between Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro and the European avant-gardes in her in-depth feature, expanding our understanding of the European avant-garde practices such as Dada and Surrealism within a Latin American context.

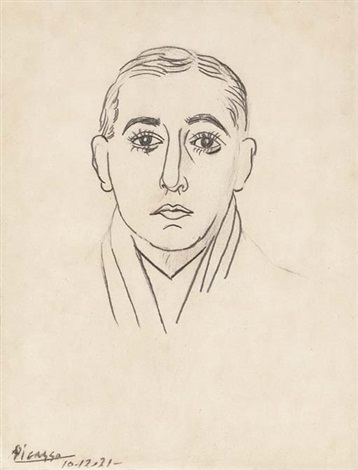

Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro (1893-1948) was one of the most prominent avant-garde writers in Latin America. Through his work as poet and editor of avant-garde journals, Huidobro contributed to the renewal of forms and imaginaries in twentieth-century poetry. The encounters and exchanges that Huidobro had throughout his life with European avant-gardes undoubtedly informed his poetic experimentation. A clear example of this influence is Huidobro’s use of the avant-garde manifesto to define his aesthetic theory known as Creationism, to disseminate his approach amidst avant-garde initiatives in Europe and to challenge the Chilean cultural scenario. As an international artistic literary form, the manifesto, perhaps the most distinctive expression of 1910s and 1920s art, was a means through which avant-garde artists contested the relationship between culture and politics and articulated programmatic statements that would position their ideas in the public sphere. The international character of the manifesto certainly resonates with Huidobro’s experience as a poet working between Latin America and Europe. As such, Huidobro’s manifestos provide an important example of transatlantic cultural and artistic exchanges, allowing us to decentre the longstanding European avant-garde narrative towards a more comprehensive perspective.

During the 1910s, Huidobro mainly focused on the development of Creationism, claiming the importance of the poet’s creative freedom for new poetic forms. Huidobro disseminated his poetic viewpoint through manifestos. Although the poet was at first sceptical of this avant-garde strategy, as literary critic Martin Puchner argues in his book Poetry of the Revolution, Huidobro finally engaged with this medium and issued several manifestos on poetry. In 1914, Huidobro delivered in Santiago his first manifesto-like speech “Non Serviam,” a proclamation of the poet’s independence from tradition, situating Creationism as an influential modernist approach in Latin American poetry. In 1916, Huidobro published in Buenos Aires his second manifesto “Arte poética,” in which the poet further developed his ideas on poetic creation already stated in his first manifesto. The following year, while living in Paris, Huidobro collaborated with the literary journal Nord-Sud, founded by French poet Pierre Reverdy and became involved in the Parisian avant-garde scene. Between Paris and Madrid, Huidobro continued with his creative and critical works, as seen in an important lecture delivered in 1921 when the poet reinforced his aesthetic views. Huidobro’s active participation in avant-garde circles was reinforced by the publication of Création, a review founded and edited by the poet between 1921 and 1924.

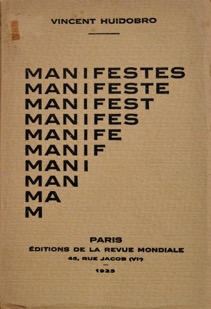

Yet Huidobro’s engagement with the manifesto was not exempt from criticism. This is revealed in “Manifesto Perhaps,” a text included in this literary journal in which the poet states “no true path and poetry skeptical of itself” ([Swindon: Shearsman], 2020: [page: 95]). The title of this text, probably an irony, shows that while Huidobro adopted the art manifesto, he was also critical of this form widely used by avant-garde schools and movements, namely Dada and Surrealism. Paradoxically, the poet continued to articulate his aesthetic approach through this medium perhaps as a strategy to position his ideas in the artistic realm. Indeed, Huidobro seems to fully adopt the manifesto for aesthetic purposes with Manifestes (fig. 1), a meta-manifesto published in 1925 that included a collection of texts in which Huidobro continued developing his aesthetic ideas on poetry and appraisal of avant-garde movements. The goal of this work seems to be clear: Huidobro aimed to situate his literary approach within the realm of modernist poetry as a response to new publications such as André Breton’s 1924 First Manifesto of Surrealism. The fact that Manifestes was written in French and published in Paris, the artistic centre at that moment, reveals that Huidobro wanted to pursue this objective conventionally.

In his works from the mid-1920s, Huidobro found a new interest in the discursive potential of the manifesto, clearly influenced by his experiences with European avant-gardes. In 1925, Huidobro returned to Chile, where he started to participate actively in the political realm. Certainly, this new interest shaped his future poetic endeavours, which were not limited to the development of his aesthetic approach. In 1925, Huidobro ran as a presidential candidate, an initiative in which he attempted to bring poetry to the immediate Chilean context. This political commitment was also seen through his pamphlets, the foundation of political journals, and later in his role as a volunteer in the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s. During this period, Huidobro created two newspapers to disseminate his political campaign: Acción. Diario de purificación nacional (fig. 2) and La reforma, created as a response to the censorship the former was subject to.

Huidobro’s critique of the Chilean political class dominated the tone of the manifesto-like texts included in these publications, claiming for the need of a local cultural transformation. In these new activities, Huidobro aimed to bring the avant-garde force for renewal to the social and political realm or, following Peter Burger’s theory of the historical avant-gardes, to integrate art into the praxis of life. In contrast to the early manifestos that mainly focused on his aesthetic view, his political commitment revealed the avant-garde attitude of using art and poetry as a tool for social change. Furthermore, Huidobro’s manifestos in Santiago, Buenos Aires, Paris and Madrid and his political initiatives in Chile indicate an attempt to reinforce cultural nodes where avant-garde attitudes dialogue. The displacement that Huidobro made of the manifesto from the artistic context to the political realm seems to challenge the unidirectional understanding of the avant-garde manifesto, demonstrating that the boundaries between the artistic and political realms merged in the work of some avant-garde artists and poets.

Paulina Caro Troncoso is a doctoral candidate in History of Art at the University of Edinburgh.