^ Giacomo Balla. Page from the Futurist Manifesto of Men’s Clothing (1913)

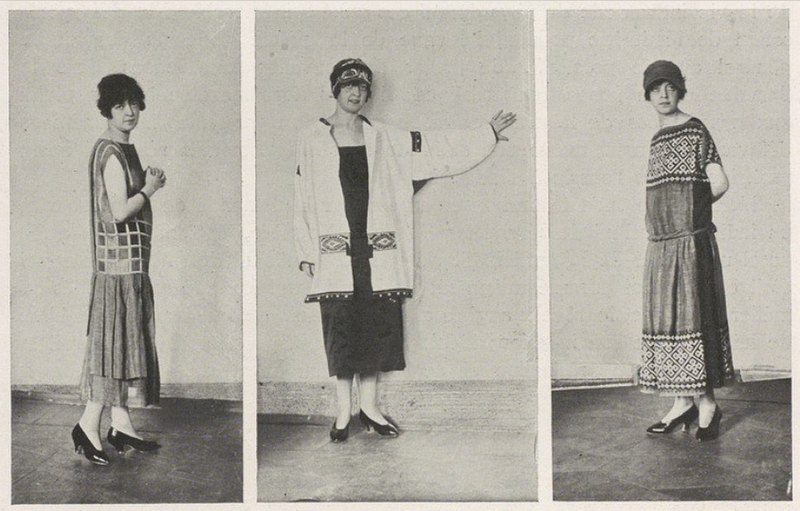

The Futurist Manifesto of Women’s Fashion in 1915 announced that dress was ‘responsible for the negation of the muscular life’ [1]. This declaration by Giacomo Balla and Vincenzo Fani (Volt) added a Futurist perspective to the growing and energetic debates among artists on the need for dress reform in the early part of the 20th Century. Their argument that clothing design must now incorporate: ‘paper, cardboard, glass, tin-foil, aluminium, majolica, rubber, fish-skin, burlap, hemp, gas, green plants, and living animals,’ [2] chimed with their colleague Prampolini’s scenographic vision for the theatre, which eradicated the need for the human subject and costume altogether. Prampolini imagined a stage inhabited by coloured gases emitting high pitched sounds, or a series of machines that would interact onstage in the absence of people. This came to fruition in 1927 in the performance Three Moments in which a fan, an elevator and a glowing jukebox were the sole performers [3].

This dual move – to eradicate human performers and to rethink dress – is typical of (usually male) modernist thinking about the theatre in the early part of the twentieth century. Frequently running through this approach is the resistance to femininity, and the rejection of supposedly unnecessary ornamentation (including theatre costume itself). This resistance emerged from the logic of craft, first articulated by thinkers such as John Ruskin and William Morris in the 19th Century. Ruskin, for example, violently condemned what he called “workmanship” – when the finish of an object calls attention to itself for its own sake – arguing that ‘any ostentation, brilliancy, or pretension of touch, any exhibition of power or quickness, merely as such – above all, any attempt to render lines attractive at the expense of their meaning, – is vice.’ [4] The modernist manifestos reforming dress, design and costume echoed these craft principles.

For example, in 1908, the architect Alfred Loos declared ornamentation a crime. In his enthusiastic denunciation of unnecessary embellishment, Loos compared the desire for pleasurable adornment as a symptom of infantile and libidinal pleasures uncurbed by social progress or racial evolution:

‘[…] what is natural to the Papuan and the child is a symptom of degeneracy in the modern adult. […] The evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament from utilitarian objects.’ [5]

Drawing on a eugenicist logic, Loos attributed the desire for ornamentation to so-called un-evolved cultures, children and women. Modernity, embodied by men, required no expressiveness through embellishment, because the autonomy that their properly evolved individuality had no need of it: ‘The nomadic herdsman had to distinguish himself by various colours; modern man uses his clothes as a mask. So immensely strong is his individuality that it can no longer be expressed in his articles of clothing. Freedom from ornament is a sign of spiritual strength.’ [6]

Loos’ objection to ornament as a form of criminal degeneracy was an extreme and racist rhetorical expression of the driving principles of modernist design. That form should follow function is the most familiar expression of a wider modernist emphasis on the stripping away of the pleasures of embellishment so associated with a degraded form of bourgeois consumerism during the 19th century. As Llewellyn Negrin argues, this continued a longstanding cultural association of ornamentation with femininity [7]. This resistance to ornamentation emerged in two ways in modernist thinking on craft and theatre costume: through new approaches to design and aesthetics; and in the reorganisation of the hierarchies of backstage craft work. This short essay explores the modernist resistance to ornamentation and its relationship to both femininity and theatre costume.

Modernist artists variously made the case for new approaches to dress as the solution to modern ills. In the new Soviet Russia for example, the designer Nadezhda Lamanova argued that dress should be: ‘comfortable, harmonious and functional,’ creating a new Soviet body that was ‘active, dynamic and conscious’ [8]. Her approach to dress reform was reflected in the practices of the stage. At the beginning of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s 1918 play, Mystery Bouffe, a chorus of working actors proclaim proudly:

The tailor of old sweated not for our waists.

All right–

However uncouth our clothing

It’s nobody else’s but ours.

Our turn!

Today, over the dust of theatres,

Scathing

Our motto begins to burn:

“renovate the world!

Stand and marvel spectators!

Curtain, Unfurl!”

[they disperse, ripping apart the curtain gaudily painted with relics of the old theatre.] [9]

Dispensing with the tailors of old, and wearing only their own clothes, these actors announced the renovation of onstage/offstage hierarchies. Here, new, unembellished clothes were imagined to dynamise the Soviet body, while theatre costumes would no longer be made by craft workers backstage.

This recalibration of theatre hierarchies can also be seen in the thinking of Mayakovsky’s collaborator, the director Vsevlod Meyerhold, who argued for the eradication of dressing-rooms, “what link should there be between the actor and the place where he is about to perform? Should he sit in his dressing room remote from the acting area, and simply arrive in time to speak his part on cue? Or is it better to place him in close proximity to the stage, so that he can easily, naturally, organically merge into the performance at the appropriate time?’ [10]. The traditional hierarchy of craft work, that so frequently, as Alice Rayner suggest ‘consigns the real labour of theatre to servitude’, was being remapped through a repudiation of ornamentation and a new approach to backstage craft [11].

In fact, this zeal for new approaches to costume had emerged much earlier in the 19th Century work of Naturalist playwrights and directors. Their resistance to ornamentation was exemplified in 1905, nine years after Anton Chekhov’s play The Seagull was first performed, when George Bernard Shaw wrote a letter to The Times protesting the presence of a dead white bird at the theatre. He complained that a woman sitting in front of him at the Royal Opera House had worn a hat, upon which she ‘had stuck over her right ear the pitiable corpse of a large white bird, which looked exactly as if someone had killed it by stamping on the beast, and then nailed it to the lady’s temple’ [12].

Shaw, that great theatrical and social reformer, objected to dead birds worn in the auditorium, just as he rejected the conspicuous consumption on display on the stage at the turn of the twentieth century. As a champion of the new Naturalist drama, he demanded that the theatre turn away from the pleasurable aspirational spectacles it had provided through the well-made play, with its well-heeled characters and fashionable furniture. This was the sort of theatre that Shaw described as

a tailor’s advertisement making sentimental remarks to a milliner’s advertisement in the middle of an upholsterer’s and decorator’s advertisement. [13]

The well-made play’s ornamental displays, affording spectators the opportunity to show off their latest headwear, were seen by Naturalist artists like Shaw, Anton Chekhov, Henrik Ibsen and Emile Zola as damaging to the moral and spiritual health of its audiences.

Indeed, as Joel Kaplan and Sheila Stowell have pointed out, the target of Naturalism was sometimes the fashion industry itself. In 1904, Edith Lyttleton’s play Warp and Woof caused a sensation in bourgeois London circles, ‘designed to demonstrate to society’s audiences the sweat and blood that went into the manufacture of fancy dress gowns.’ [14] Lyttleton exposed the fashion system’s reliance on structures of inequality that produced terrible suffering for the female sweatshop workers. Women were framed as both the perpetrators and victims of this excessive hunger for embellishment and display, and Lyttleton offered up Naturalism as a diagnostic tool of this social illness, and simultaneously as its theatrical cure.

This was a medicine that did not go down easily, however. The forensic approach that Naturalist artists took to their depiction of bourgeois life included its dress, with corsets and collars condemned for their enervating effects on the characters wearing them. Naturalism’s view of clothing as a causal ‘environment’ for bourgeois behaviour, without the sugary coating of aspirational luxury, made the English critic Clement Scott recoil in disgust, complaining that the first English production of Hedda Gabler, ‘was still far too like Balham to be pleasant’. [15]

Of course, Lyttleton’s play emerged in a moment populated by countless Fabian tracts decrying the sweatshop system and its treatment of female workers. The anxieties about the effects of factory work on female workers has had an important place in craft theories, but the gender politics of this thinking were often complicated. The desire to ‘protect’ female workers often emerged alongside the desire to police their sexual decorum. Early craft polemicists, such as Peter Gaskell in 1836, expressed deep anxieties about the gendered consequences of automation, raising concerns about ‘the animal enjoyments, the sensual indulgences’ [16] and ‘the almost entire extinction of sexual decency’ [17] brought about by factory work. This emerging moral depravity, he argued, was brought about by increasing disposable income, where ‘cottages were exchanged for mansions’ [18] and the introduction of unskilled female labour to factories which meant that women were ‘freed from domestic discipline’, and factory work had brought about ‘the separation of man and wife during the hours of labour’ [19].

Craft thinking through the 19th century frequently reiterated these gendered assumptions. John Ruskin blamed female consumers particularly for the mass production of clothes, due to their wasteful and immoral desire for ornamentation. Meanwhile, William Morris imagined a utopian futuristic world in his 1890 novel, News from Nowhere, in which Londoners had eschewed automation in favour of craft-based equality. In this perfect world, housework had become a dignified art, in which

it is a great pleasure to a clever woman to manage a house skilfully and to do it so that all the house-mates about her look pleased, and are grateful to her […] and then, you know, everybody likes to be ordered about by a pretty woman. [20]

The emphasis on the home made in the argument for the autonomy and agency of skilled craft-work often maintained other gendered and domestic status quos.

Indeed, making from home did not necessarily improve the working conditions of women. Certainly, in the case of the theatre, homeworking did female costume workers no good. The mid-19th century London theatre was characterised by the exodus of costume makers from its buildings into their own homes. Tracy Davis sketches this shift: ‘In 1865, Drury Lane employed ninety-three dressers/ dressmakers, but only twenty in 1881, all of whom were dressers not seamstresses’ [21]. Through an increasing process of specialisation and sub-contraction, the manufacture of costumes left the theatres and was sent out to small firms, often based in women’s homes. As a result, while the technical work of set building and lighting remained in the theatre and was dominated by men, women’s backstage costume work left the building. And, as Davis points out, this meant that men’s work backstage unionised far more quickly – and claimed better pay and conditions – than women’s: ‘Male trades remained closest to the production processes. Not surprisingly, these operatives were the first to organize. […] Women’s trades were practiced outside the theatres, making it much more difficult to unionize’ [22]. The effects of this difference can still be seen in the unequal ways in which these backstage crafts continue to be valued – and renumerated – today.

So, even while Mayakovsky denigrated the ‘tailors of old’, the move to re-insert backstage costume craft into theatre buildings was actually a progressive move at the start of the twentieth century. When William Archer and Harley Granville Barker (close collaborators of George Bernard Shaw) published their Scheme and Estimates for A National Theatre in 1908, they made the radical gesture of including a wardrobe department within their vision for a national theatre, restoring costume work to their imagined building. However, despite this radical vision, Granville Barker in his Preface to the publication, still felt it necessary to express his ambivalence toward the value of costume. He, once again, aligned an interest in ornamentation with the degraded values of the feminine, recalling:

A most unhappy afternoon at the Court Theatre, when a certain actress, Bernard Shaw, and I passed in review a perfect kaleidoscope of scenery and clothes. […] Shaw protested to the bitter end that he had an opinion of his own; but after two or three hours of this torture I was ready to confess that I neither knew green from pink nor cared. […] I sometimes think that the only reliable figures about ladies’ modern dresses are contained in the bills for them. [23]

When the National Theatre finally opened in 1976 on the Southbank it did indeed include an entire floor dedicated to the costume department, whose team of 47 makers, dyers, buyers, stock controllers, supervisors, dressers, wardrobe and hire department work there now.

The majority of these workers are women. The work that they do is hugely skilful, committed and technically challenging. Theatre costume – and its workers – continues to be almost entirely overlooked and undervalued by critics, academics and other theatre workers. It may be that another moment of dress reform is necessary today – this time rejecting the modernist rejection of ornamentation and theatre costume, seeing them instead, as crimes worth committing.

Aoife Monks

Queen Mary University of London, 2020.

References / Further Reading

[1] Paulicelli, Eugenia. “Fashion and Futurism: Performing Dress.” Annali D’Italianistica, vol. 27, 2009, pp. 187–207, p. 188.

[2] Paulicelli, ibid, p. 188.

[3] See https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/enrico-prampolini

[4] Ruskin, ‘Execution’, SELECTIONS FROM THE WORKS OF JOHN RUSKIN (BOSTON, NEW York, CHICAGO, SAN FRANCISCO: The Riverside Press Cambridge, 1908), pp. 145-147, p. 146.

[5] Alfred Loos, ‘Ornament and Crime’, Programs and Manifestoes on Twentieth Century Architecture, ed. by Ulrich Conrads, (Cambridge Mass: MIT press: 1970), p. 20, emphasis original.

[6] Loos, ibid., p. 24.

[7] Negrin, Appearance and Identity: Fashioning the Body in Postmodernity (Palgrave: 2008), p. 118.

[8] See Djurdja Bartlett (2017) ‘Nadezhda Lamanova and Russian Pre-1917 Modernity: Between Haute Couture and Avant-garde Art’, Fashion Theory, 21:1, 35-77,

[9] See Mayakovsky: Plays https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=eqSQ9YG3f24C&printsec=frontcover&dq=mayakovsky&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjR_dCD3anqAhVQXsAKHXchCFsQ6AEwAHoECAEQAg#v=onepage&q=mayakovsky&f=false

[10] Meyerhold, Meyerhold on Theatre (London: Methuen, 1972), p. 149.

[11] Rayner, Alice. “Rude Mechanicals and the ‘Specters of Marx.’” Theatre Journal, vol. 54, no. 4, 2002, pp. 535–554.

[12] Tessa Boase, Mrs Pankhurst’s Purple Feather: Fashion, Fury and Feminism And Women’s Fight for Change (London: Aurum Press, 2018), p. 147

[13] Christopher Wixon, Bernard Shaw and Modern Advertising: Prophet Motives, (London: Springer, 2018), p. 7.

[14] Kaplan and Stowell, Theatre and Fashion: Oscar Wilde To The Suffragettes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. 84.

[15] Ibid, p. 46.

[16] Gaskell, ‘Artisans and Machinery: The Moral and Physical Conditions of the Manufacturing Population Considered With Reference To Mechanical Substitutes for Human Labour’ in Glenn Adamson ed. The Craft Reader (Oxford and New York: Berg, 2010), pp. 55-60, p. 56.

[17] Ibid., p. 57.

[18] Ibid.

[19] ibid.

[20] William Morris, News From Nowhere And Other Writings (London: Penguin Books, 1993, p. 94.

[21] Davis, The Economics of the British Stage, 1800-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 320.

[22] Ibid, pp. 322-3.

[23] William Archer and Granville Barker, Scheme and Estimates For A National Theatre (New York: Duffield Company, 1908), pp. ix-x.